Effortful Control, Sensory Processing, and Executive Function: Research and Practical Strategies

Effortful control is a vital skill that helps students manage their emotions, stay focused, and complete tasks, all of which are essential for academic and social success. As educators and occupational therapists, understanding how effortful control relates to sensory processing and executive function can offer new strategies to support children in the classroom. Recent research has provided valuable insights into these relationships, highlighting the importance of addressing sensory needs to promote better self-regulation and learning outcomes. Learn more about what effortful control is, what the latest research says about its connections to sensory processing and executive function, and how to improve this skill in students.

What Is Effortful Control?

Effortful control is the ability to regulate one’s emotions, behaviors, and attention in order to achieve a goal. It’s a critical aspect of temperament that enables students to stay focused, delay gratification, and manage impulses, which are all necessary for academic success and positive social interactions.

Key characteristics of effortful control include:

- Emotional regulation: Managing emotions when frustrated or challenged.

- Behavioral control: Inhibiting impulses and staying on task.

- Attention and focus: Concentrating on a task even in distracting environments.

Students with strong effortful control can:

- Delay gratification: Wait for a reward or complete less desirable tasks before engaging in preferred activities.

- Maintain focus: Stay engaged in a task despite distractions.

- Control impulses: Resist the urge to act impulsively, especially when it disrupts learning or social interactions.

On the other hand, students with low effortful control may:

- Struggle with impulsivity: Act without thinking, interrupt others, or rush through tasks.

- Have difficulty focusing: Lose attention easily in busy or overstimulating environments.

- Experience emotional outbursts: React strongly to frustration or disappointment.

What Does the Research Say About Effortful Control, Sensory Processing, and Executive Function Skills?

A 2024 study conducted by Rachel B. Diamant and Natasha Smet examined the relationships between sensory processing, effortful control, and executive function in school-aged children. Their findings shed light on how these factors interact and influence a child’s ability to succeed in the classroom.

1. Sensory Processing and Executive Function

- The study found that children with typical sensory processing (i.e., appropriate responses to sensory stimuli like sound, touch, or movement) tend to have stronger executive function skills. These skills include the ability to plan, focus, and shift attention between tasks.

- On the other hand, children who are more sensitive to sensory stimuli—such as being overwhelmed by loud noises or visually busy environments—may struggle with executive function. These children are more likely to display impulsivity and have difficulty maintaining attention.

2. Effortful Control and Executive Function

- Children with higher levels of effortful control also show stronger executive function skills. These children can manage their emotions and impulses more effectively, making them better at problem-solving, focusing, and organizing tasks.

- Conversely, children with lower levels of effortful control often experience challenges with executive function. They may struggle to stay on task, regulate their emotions, or shift between activities when needed.

3. Sensory Seeking and Effortful Control

- The study also identified a link between sensory-seeking behaviors and effortful control. Children who frequently seek sensory input (e.g., moving around, touching things, or craving sensory stimulation) often have more difficulty with effortful control. Their constant need for stimulation can interfere with their ability to focus and control impulses, particularly in structured environments like the classroom.

These findings highlight the close relationship between sensory processing, effortful control, and executive function, suggesting that addressing sensory needs can help improve a child’s ability to self-regulate and perform better academically.

Sensory Choice Boards

How to Improve Effortful Control in Students

Effortful control can be nurtured and improved through targeted strategies, both in the classroom and in therapy settings. Here are several practical approaches to help students build and strengthen their effortful control:

1. Practice Delayed Gratification

Teaching students to wait for rewards helps them develop patience and self-control. Some ways to incorporate this into the classroom include:

- Token systems: Students earn tokens or points throughout the day for positive behavior, which they can trade for rewards at the end of the week.

- Games involving waiting: Play games like “Red Light, Green Light” or “Simon Says,” which require students to wait for the right moment to act, fostering impulse control.

2. Break Tasks into Smaller Steps

Large tasks can overwhelm students with low effortful control, leading to frustration or avoidance. Breaking tasks down into smaller, manageable steps helps maintain focus and reduce overwhelm:

- Checklists: Provide visual checklists to help students track their progress and break tasks into simple, actionable steps.

- Chunking assignments: For longer tasks, divide them into smaller portions with clear goals and deadlines to help students stay on track without feeling overwhelmed.

3. Provide Opportunities for Choice

When students feel they have some control over their activities, they are more likely to engage and practice self-regulation:

- Choice boards: Let students choose between different tasks or methods of completing an assignment to give them a sense of ownership.

- Reward choice: Allow students to choose their own rewards, increasing motivation to stay focused and complete tasks.

4. Teach Emotional Regulation Techniques

Helping students manage their emotions is key to improving effortful control. When students can control their emotions, they are better equipped to stay focused and complete tasks.

- Mindfulness exercises: Introduce mindfulness practices like breathing exercises or guided meditation to help students calm down and regulate their emotions.

- Emotion labeling: Encourage students to identify and label their emotions, which can help them understand and manage their reactions more effectively.

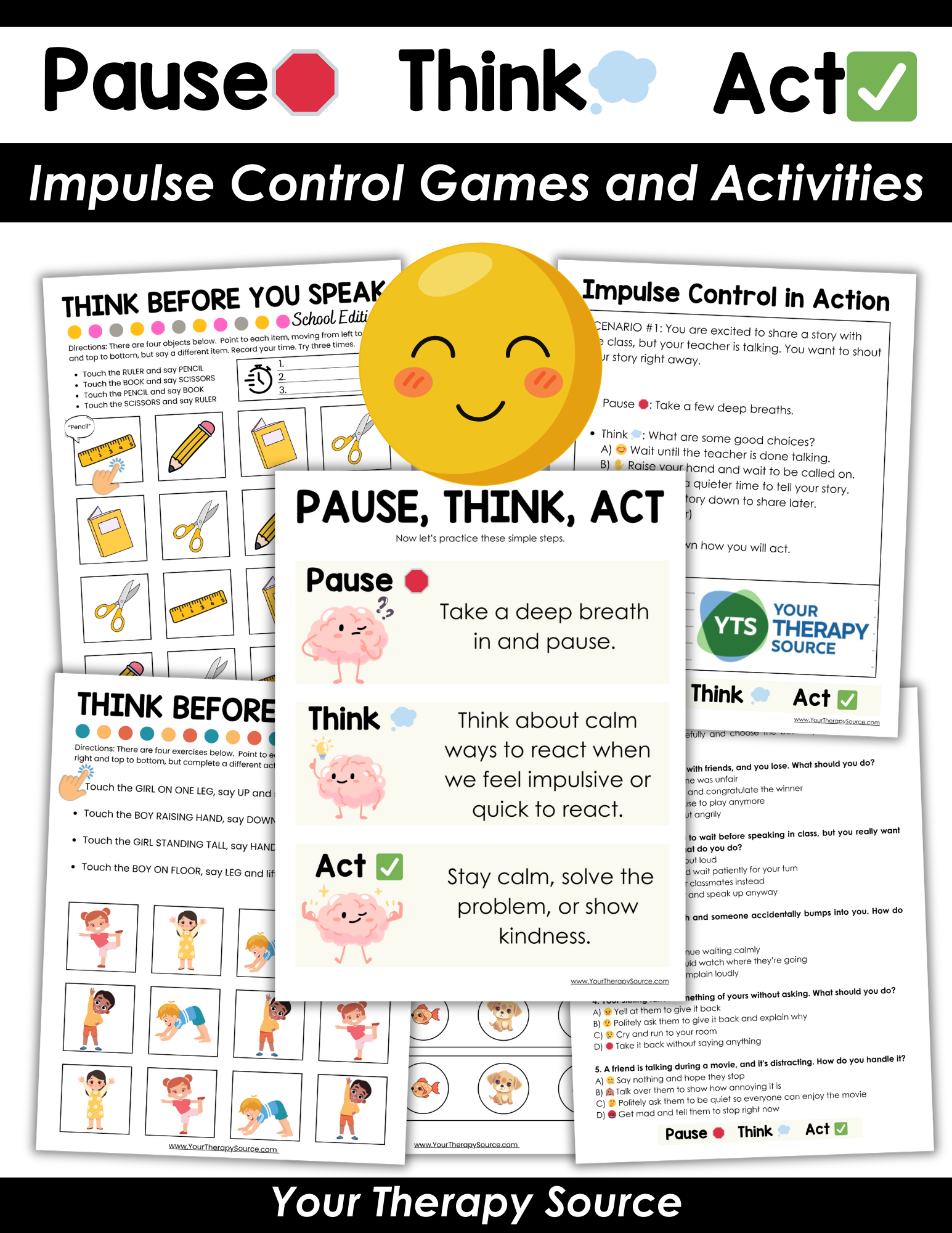

5. Use Games That Promote Self-Control

Games that require turn-taking, attention, and patience are great for building self-regulation and effortful control:

- Board games: Games like “Chutes and Ladders” or “Candyland” teach students to wait their turn and manage frustration when setbacks occur.

- Memory games: Activities that challenge students to remember details, such as memory matching games, promote sustained focus and attention.

6. Model and Reinforce Effortful Control

Students often learn self-regulation by observing adults. Modeling effortful control in daily interactions can help students adopt these behaviors:

- Think-alouds: Demonstrate effortful control by verbalizing how you manage frustration or stay focused on tasks. For example, say, “I want to finish my work, but first I’ll take a deep breath and focus on one thing at a time.”

- Positive reinforcement: Praise students when they exhibit effortful control, such as waiting their turn or staying focused, to reinforce these behaviors.

7. Incorporate Physical Activity and Sensory Breaks

Physical activity and sensory breaks can help students with low effortful control reset their focus and energy levels:

- Movement breaks: Integrate short, structured physical activities between lessons to help students release excess energy and refocus.

- Sensory tools: Offer sensory tools like stress balls, fidget spinners, or tactile cushions for students who need additional sensory input to stay engaged.

Key Points

Effortful control is an essential skill for academic success, allowing students to manage their behavior, focus on tasks, and regulate their emotions. Understanding how effortful control is connected to sensory processing and executive function enables educators and therapists to develop targeted interventions that support student success.

- Effortful control is the ability to regulate emotions, behaviors, and attention, essential for success in academic and social environments.

- Sensory processing plays a critical role in a child’s ability to focus and manage impulses. Children with typical sensory processing tend to have stronger executive function skills, while children with heightened sensitivity may struggle with attention and self-regulation.

- Executive function refers to skills like planning, focusing, and problem-solving. It is closely linked to both sensory processing and effortful control, with strong executive function leading to better task completion and behavioral management.

- Children who seek sensory input often have more difficulty with effortful control, as their need for stimulation can interfere with their focus and impulse regulation.

- Delayed gratification can help improve effortful control. Token systems, earning privileges, and games that require waiting are useful strategies to teach patience and self-control.

- Breaking tasks into smaller steps helps students with low effortful control stay focused and avoid feeling overwhelmed.

- Offering choices allows students to practice decision-making and self-regulation, promoting a sense of ownership and responsibility for their actions.

- Emotional regulation techniques such as mindfulness exercises and emotion labeling are effective tools to help students manage their emotions and stay focused on tasks.

- Games that promote self-control like board games and memory games can be used to strengthen patience, attention, and impulse control in a fun, engaging way.

- Physical activity and sensory breaks provide opportunities for students to reset their focus and manage their energy levels, improving overall self-regulation.

By implementing strategies like delayed gratification exercises, emotional regulation techniques, and sensory support, educators can help students strengthen their effortful control, leading to better focus, self-regulation, and overall academic performance.

Reference:

Diamant, R. B., & Smet, N. (2024). Relationships Between Sensory Processing, Temperament Characteristics for Effortful Control, and Executive Function in School-Age Children. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.2164